The Emotional Impact of War Memorials: Why They Matter

3/15/2025

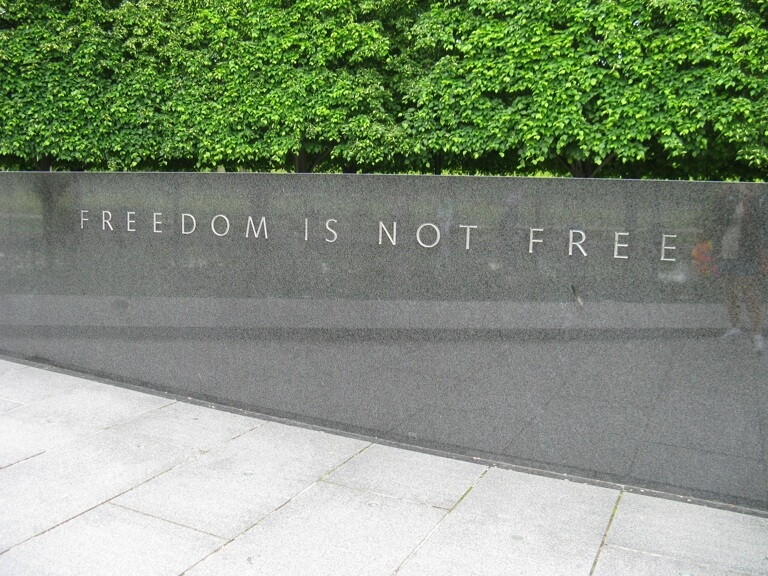

War memorials stand as silent sentinels across the American landscape, from small-town squares to the grand expanse of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. These monuments of stone, steel, and bronze do far more than simply mark historical events—they serve as powerful emotional anchors that connect us to our shared past and help us process the complex legacy of war.

The Psychology of Remembrance

When we visit war memorials, we engage in a deeply human act of remembrance. These sites are designed not just to inform but to evoke emotional responses that help us connect with historical events that might otherwise feel distant or abstract. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., designed by Maya Lin, exemplifies this approach. Its black granite walls, inscribed with the names of over 58,000 Americans who died or remain missing, create a reflective surface where visitors see themselves alongside the names of the fallen—a powerful visual metaphor for the connection between past and present.

Dr. Edward Linenthal, a professor of history at Indiana University, explains that “memorials serve as sites of public memory where communities negotiate the meaning of traumatic events.” This negotiation happens on both collective and individual levels. For communities, memorials provide a shared space to acknowledge sacrifice and loss. For individuals, especially those with personal connections to the commemorated events, memorials offer a tangible place to process grief and find meaning in loss.

Beyond Names and Dates

The most effective war memorials transcend simple chronology to capture something essential about the human experience of conflict. Consider the Korean War Veterans Memorial, with its 19 stainless steel statues depicting a squad on patrol. The figures, slightly larger than life-size, wear ponchos that appear to billow in the wind, creating an eerie sense of movement. Their faces, etched with tension and vigilance, communicate the psychological reality of war in ways that no textbook could.

”What makes these memorials so powerful is that they don’t just tell us what happened—they make us feel something about what happened,” says Sarah Wagner, an anthropologist who studies commemoration practices. “They translate historical events into emotional experiences.”

This emotional translation serves multiple purposes. For veterans, memorials can validate experiences that may have been difficult to communicate to those who weren’t there. For families of the fallen, they provide recognition of their loved ones’ sacrifice. For the general public, they create an emotional entry point into understanding the human costs of war.

Healing Through Remembrance

War memorials also serve a therapeutic function, particularly for those directly affected by conflict. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, initially controversial for its non-traditional design, has become a place of pilgrimage and healing for many veterans who returned home to a divided nation that often failed to distinguish between the war and those who fought in it.

”The Wall,” as it’s commonly known, receives millions of visitors annually, many of whom leave personal items—photographs, letters, dog tags, combat boots—as offerings. These items (over 400,000 to date) are collected by the National Park Service and preserved as part of the memorial’s growing archive. This practice of leaving mementos represents a form of dialogue between the living and the dead, a way of maintaining connections across time.

Jan Scruggs, the Vietnam veteran who spearheaded the creation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, has observed that “the memorial has become a place where the living and the dead can come together.” This coming together facilitates a kind of collective healing, allowing for the acknowledgment of wounds that may have remained unaddressed for decades.

Evolving Meanings

The emotional impact of war memorials isn’t static—it evolves over time as new generations bring their own perspectives and as societal attitudes toward particular conflicts shift. The World War II Memorial, dedicated in 2004, arrived at a moment of renewed appreciation for the “Greatest Generation,” spurred in part by books like Tom Brokaw’s work of the same name and films like “Saving Private Ryan.”

By contrast, memorials to the Vietnam War emerged from a context of national division and uncertainty. The Korean War—often called “The Forgotten War”—received its national memorial only in 1995, four decades after the armistice. These varying timeframes between events and their commemoration reflect changing emotional needs and historical perspectives.

”Memorials don’t just reflect history—they actively shape how we understand it,” notes Kirk Savage, author of “Monument Wars.” “They’re not neutral records but interpretive acts that emphasize certain aspects of events while downplaying others.”

This interpretive quality means that war memorials can become sites of contestation as well as commemoration. Debates about who and what should be memorialized—and how—reveal deeper questions about national identity and values.

Creating Personal Connections

Perhaps the most profound emotional impact of war memorials comes from their ability to transform abstract statistics into recognizable human lives. The practice of listing individual names, pioneered at a national level by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and now common in newer memorials, personalizes the cost of war.

When visitors search for specific names—perhaps a family member, a friend, or someone from their hometown—they engage in an act of personal connection that makes the historical real and immediate. The rubbing of names from the Vietnam Wall, for example, allows visitors to take home a tangible connection to a specific individual.

”There’s something powerful about seeing a name,” says Kristin Ann Hass, author of “Carried to the Wall: American Memory and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.” “It reminds us that behind every statistic was a person with hopes and dreams and people who loved them.”

Digital Extensions of Emotional Impact

In our increasingly digital world, the emotional impact of war memorials is extending beyond their physical locations. Virtual tours, online databases of names, and digital archives of items left at memorials allow people who cannot visit in person to form emotional connections with these sites of memory.

The American Battle Monuments Commission, for example, maintains digital databases that allow families to locate the graves or names of loved ones at overseas cemeteries and memorials. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund’s “Wall of Faces” project aims to collect photographs of every person whose name appears on the Wall, creating visual connections to the names etched in stone.

These digital extensions don’t replace the experience of physical presence at a memorial but offer new ways to engage emotionally with the histories they commemorate.

The Continuing Relevance

As the United States continues to navigate the aftermath of more recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the emotional function of war memorials remains vitally important. New memorials will eventually take shape, reflecting our evolving understanding of these conflicts and providing spaces for a new generation of veterans and families to find recognition and healing.

The emotional impact of war memorials reminds us that history isn’t just something that happened in the past—it’s something that continues to live within us, shaping our understanding of ourselves as individuals and as a nation. By creating spaces that acknowledge sacrifice, facilitate grief, promote healing, and encourage reflection, war memorials help us navigate the complex emotional legacy of war.

In a society that often moves quickly from one news cycle to the next, these places of remembrance ask us to pause, to feel, and to consider the full human cost of conflict. Their emotional power lies in this invitation to connect—across time, across experience, and across the divide between the living and the dead.

As Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, has said: “I had an impulse to cut open the earth… an initial violence that in time would heal. The grass would grow back, but the cut would remain, a pure flat surface in the earth with a polished, mirrored surface, listing the names of those who had died.”

This metaphor of a wound that remains visible even as healing occurs captures the essential emotional function of war memorials. They don’t erase painful histories but provide spaces where those histories can be acknowledged, felt, and integrated into our ongoing national story.